Leducate Explains: The Rules of Criminal Evidence

Hint - key terms are defined. Just click on the blue words to see their definitions!

In this article, we look at some of the rules that the court will apply when someone tries to put forward evidence in a trial. This is the second article in our criminal evidence law series, so be sure to check out the first article before reading this one!

Rules of evidence

At its simplest, the rules of evidence can be reduced to the acronym, RARP. The court will apply these rules in deciding whether or not it will consider the evidence that a party to the trial wishes to rely on. The court will, therefore, ask itself:

Is the evidence relevant? Is the evidence admissible? Is the evidence reliable? How useful is the evidence (probative value)?

Is the evidence relevant?

The evidence must be such that it is able to support, prove or shed light on the existence of a fact that is in issue at trial. So, relevance is really about two things. First, there must be some logical connection between the evidence and the fact it is offered to prove or disprove. For example, if it is asserted that a man was running away from the crime scene, CCTV footage would be relevant if it shows him running. Also, any witness statements about the man running or not would be relevant. But an IQ test showing his level of intelligence would not be relevant because it cannot tell you anything about whether he was in fact running or not. Second, the evidence must be regarding the fact being discussed. For example, a man charged with doing 75mph in a 60mph zone may state, in his defence, that he was in an 80mph zone. Here, the speed of the car is not being disputed; rather the issue is what the zone limit is. Any evidence of the speed of his car is, therefore, not relevant.

🔎 Key point: Evidence that is not relevant will not be considered by the court and should not be heard by the jury. If the evidence is relevant, the next thing the court will consider is whether it is admissible.

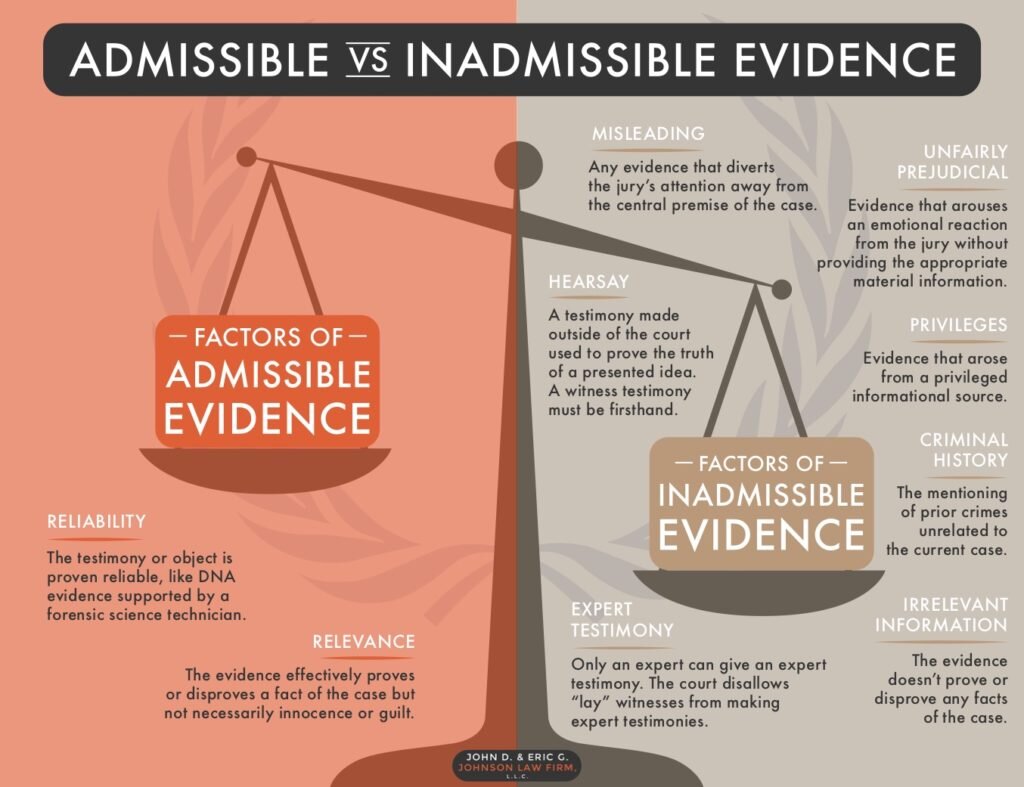

Source: Eric Johnson Law

Is the evidence admissible?

There is a truckload of rules about the sort of evidence that the court will and will not consider. These rules have developed over time according to the common law. Although in many jurisdictions, including the UK, these rules have been written into legislation(s). These rules can be quite puzzling to understand and many may find it difficult to comprehend why evidence that is relevant can be kept away from the jury. The overarching reason for this is the preservation of justice. As you can see from the diagram above, hearsay evidence usually cannot be relied upon in court. This is where a witness gives evidence of something they have not seen themselves (i.e. what someone else has told them about). For example, if in your evidence you state that your friend told you about a car crash they saw, that would be hearsay evidence. But, as with all rules, there are exception(s). One of the most important exceptions to hearsay evidence is confessions – if someone confesses to a crime and another person overhears it, that person can then come forward to the court to produce that as evidence.

🔎 Distinguish:

Direct evidence – I saw him enter the bank with a gun in his hand and shout “hands up, nobody move, nobody gets hurt”.

Hearsay evidence – I know he entered the bank with a gun in his hand and shouted “hands up, nobody move, nobody gets hurt” because my friend, Susie, saw it.

Source: Todays News Post

The criminal history or character of a person is another thing that usually cannot be relied upon in court. The criminal history of a person must not be made known to the jury. You may be sitting there thinking: Well, that’s crazy! Shouldn’t the jury know that a person has been jailed three times for similar offences? The answer is simply no — the fact that a person has been convicted of similar offences in the past actually tells us nothing unless, of course, there is some ‘signature’ aspect of the crime that links those offences committed in the past to that of the present. A ‘signature aspect’ could be, for example, the way in which a serial murderer disposes of bodies. The character of a person is also somewhat of a sensitive topic in criminal trials. In dishonesty or fraud-related offences, for example, a lawyer may wish to bring in evidence that accentuates an accused person’s tendency towards behaving dishonestly to show that they lack general credibility in what they are saying (and therefore, the jury should think twice before considering what is being said). Generally, the court will not allow this unless it can be shown that the accused person has behaved in a “reprehensible” manner (i.e. behaved in a very bad way, sometimes to the extent of being morally wrong).

The court will also tread carefully when it comes to witness opinions. Witnesses are not allowed to just give their opinions about things — this is not Twitter! They can give evidence about what they observed but, ultimately, it is for the jury to decide what that all means. Having said that, the court will allow opinions from an expert (i.e. someone who has expertise that the court does not have) — for example, a doctor, DNA analyst or handwriting expert. Whilst an expert usually would not have witnessed a crime for themselves, they will be able to contribute by evaluating information and providing an independent (unbiased) opinion about things based on their knowledge and expertise. A handwriting expert, for example, might be asked to analyse important bank documents and verify in court that a person’s signature has been forged.

Is the evidence reliable?

Evidence can be unreliable for a number of reasons. A witness may have a history of lying to the police, or they may have made a bunch of statements outside the court that contradict those said in court. There may even be evidence to show that the witness has been threatened or offered a reward relating to their evidence. In some instances, the witness may have a close relationship with the accused person that it would be difficult or impossible for them to give impartial evidence. In criminal trials, lawyers will spend quite a lot of time trying to show the jury that the evidence put forward by the other side is unreliable for one reason or another.

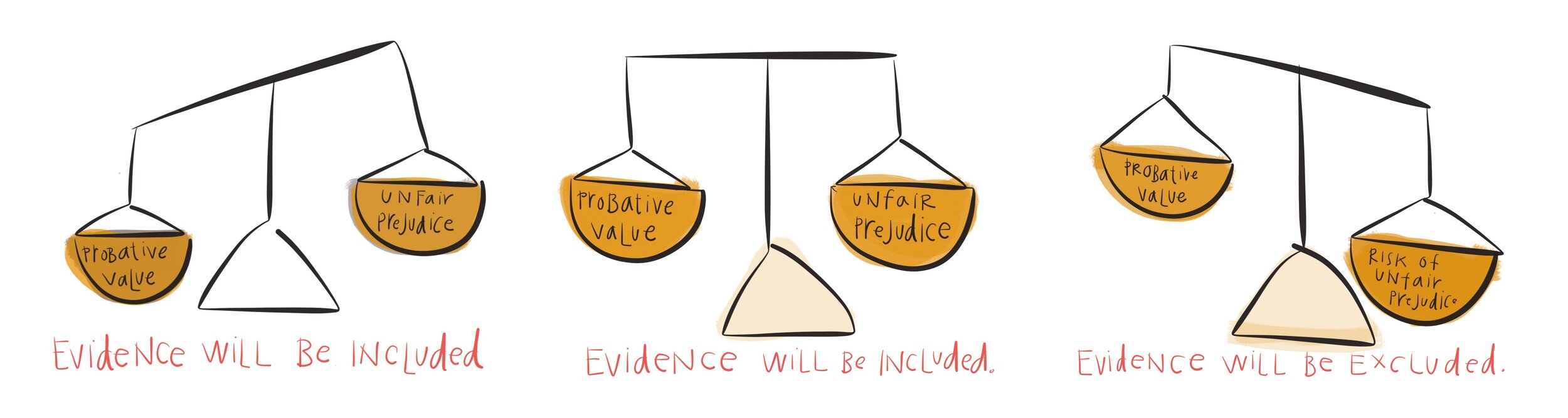

Credit: Margaret Hagan

How useful is the evidence (probative value)?

Evidence needs to be useful if it is going to prove or disprove something during trial, especially something that is contentious – this is known as the ‘probative value’ of evidence. If evidence is not useful, then its purpose or existence in a trial is met in vain. For example, a lawyer may want to adduce (use) a piece of evidence if they feel that it is going to help their case in any way (or, in some instances, win their case!) You may be wondering, well isn’t probative value the same thing as relevance then? Not quite, but they certainly go hand in hand. You can think of probative value in terms of how heavy a piece of evidence is going to weigh in a case on a scale of 0 to 100. If the evidence weighs close to 0, the court is very unlikely to consider it. If, say, it weighs around 80, the court is more likely to want to consider it. As seen in the diagram above, the probative value of a piece of evidence is always going to be weighed against whether or not it has some sort of prejudicial effect on the criminal trial process as a whole. A judge can certainly exclude the evidence if it is thought to impact negatively upon the fairness or integrity of the case at hand.

Conclusion

In this article, we have seen that there are several hurdles that a piece of evidence has to jump over in order to be allowed for consideration by the court. Every piece of evidence seeking to be admitted in a criminal trial must fulfil RARP (Relevant, Admissible, Reliable and Probative Value). Even where a piece of evidence is shown to be relevant and admissible, it can be chucked out by the court if it is found to be unreliable or lacks the ability to prove or disprove an important point. As tedious as it sounds, this is absolutely crucial to ensure the preservation of justice, as well as uphold fairness and integrity in a criminal trial.

Written by Veera Poonganesan

Glossary box:

Common law - A body of legal rules that have been made by judges, as opposed to what is stated in legislation.

Legislation – Law that is passed by Parliament. For example, the Criminal Justice Act (CJA) 2003 is a piece of legislation that Parliament passed in 2003.

Signature aspect – Something that is a unique and integral part of the offender's behaviour, especially for violent crimes. For example, the way in which a serial murderer disposes of bodies.

Adduce - A legal term for using something as evidence.